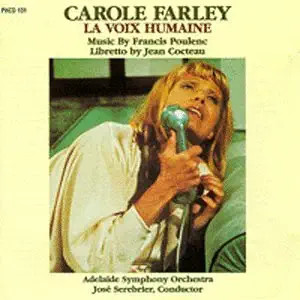

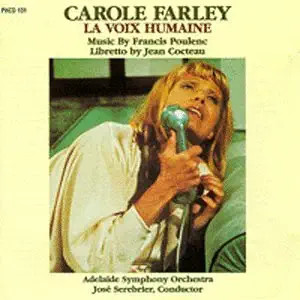

La Voix Humaine

Carole Farley, Soprano

PHCD131 | Phoenix CD

| Name | Credit | |

|---|---|---|

|

Francis Poulenc | Composer |

|

Carole Farley | Soprano |

|

Jose Serebrier | Conductor |

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Jose Serebrier, conductor

PHCD131 | Phoenix CD

| Name | Credit | |

|---|---|---|

|

Francis Poulenc | Composer |

|

Carole Farley | Soprano |

|

Jose Serebrier | Conductor |

PHCD 131

Francis Poulenc, La Voix Humaine (Mono-Drama in one act)

Carole Farley, soprano

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

Jose Serebrier, conductor

PHCD131 presents Francis Poulenc’s powerful monodrama La Voix Humaine, performed by soprano Carole Farley with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra conducted by José Serebrier. Poulenc’s setting of Cocteau’s one‑act drama captures the raw emotional landscape of a woman’s final telephone conversation with her lover. Farley’s interpretation brings immediacy and expressive depth to this landmark 20th‑century work, supported by Serebrier’s sensitive and atmospheric orchestral direction.

Jean Cocteau used the simplest of plots and minimal theatrical elements to dwell upon a deep, wide range of unspoken human emotions. The old story of the abandoned young woman desperately but unsuccessfully trying to regain her lover, who has decided to marry another woman in two days, has been transformed by Cocteau in a theatrical tour-de-force full of drama, tension and anguish. For 50 minutes, this “elegant young woman” pleads with her lost lover, cries, reminisces incoherently, lies, suffers and loses reality, slowly but inexorably falling into a state of depression and irreparable sadness. She seems, finally, calm and reconciled, but as she protests for the last time her eternal love and devotion to her ex-lover, she strangles herself with the telephone cord.

The play was premiered at the Paris Comedie-Francaise by Berthe Bovy in 1932, but the Poulenc version only came to life in 1959 at the Opera Comique, with Denise Duval. Cocteau was enchanted. He wrote to Poulenc: “My dear Francis, you have found the only way to say my text.” Indeed, Cocteau had avoided the long poetic flights, using instead interrupted, almost staggered prose to communicate this woman’s anguish. Poulenc seems to have captured every nuance, avoiding the easy flowing melodies, and concentrating on the expressive elements of the human voice, whispers, sighs, sobbing phrases. The theatrical tour-de-force became a real concerto for soprano, with great musical difficulties added to the challenge of supporting a long winding monologue. On the almost bare stage there is no action to speak of, just a young woman on a couch, and a telephone and, like in Wagner, the drama unfolds inside the character, while it is depicted in the music. Unlike Wagner, Poulenc has avoided the heated lyricism, following instead a pattern of broken prosaic sentences, and a drastic, almost hysterical change of moods.

The obvious precedent would be Schoenberg’s Erwartung, also a dramatic monodrama for solo soprano. However, there are hardly two more different works. Schoenberg’s lyric, expressionist work is worlds apart from Poulenc’s transparent, realistic vision. The common factor is the enormous difficulty for a single actress-singer to support the lone drama on an empty stage.

More works by Francis Poulenc: https://phoenixcd.com/composer/francis-poulenc/