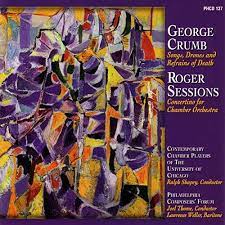

Shapey, Ralph

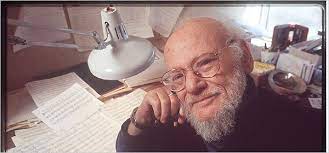

Shapey was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He is known for his work as a composition professor at the University of Chicago, where he taught from 1964 to 1991 and where he founded and directed the Contemporary Chamber Players. Shapey studied violin with Emanuel Zeitlin and composition with Stefan Wolpe. He served in the United States Army in World War II before moving to New York City, where he worked as a violinist, composer, conductor, and pedagogue. In 1963, he conducted the orchestra and chorus at the University of Pennsylvania before accepting his position in Chicago.[1][2]

Shapey was made a MacArthur Fellow in 1982. Upon hearing the news via a telephone call, Shapey was initially skeptical; he reportedly asked, “Which of my friends or enemies put you up to this?” and slammed down the receiver.[2]

Although Shapey’s style is characterized by modernist angularity, irony, and technical rigor, his coincident concern for sweeping gesture, frenetic passion, rhythmic vitality, lyrical melody, and dramatic arc recall Romanticism. Shapey was dubbed by the critics Leonard B. Meyer and Bernard Jacobson as a, “radical traditionalist,” which pleased him immensely—he held a deep respect for the masters of the past, whom he regarded as his finest teachers.[citation needed]

The French-American composer Edgard Varèse was among Shapey’s most important influences. Both composers shared a fascination with unusual sonorities, counterpoint masses, and the outer extremes of pitch space. The coordination of static “sound blocks” in Shapey’s music also reminds one of another French composer, Olivier Messiaen, though Shapey reportedly found Messiaen’s music saccharine and maudlin.[citation needed]

Although comparisons are useful, Shapey’s compositional voice is undoubtedly personal and distinctive. Many listeners would call his music[weasel words] “atonal,” but Shapey himself denied the label. He considered himself a tonal composer, and indeed his work, though couched in a highly dissonant harmonic idiom rich in interval classes 1 and 6, does adhere to certain organizational features of tonal music, including pitch hierarchy and object permanence.[citation needed]

Shapey’s Concerto for Cello, Piano, and String Orchestra was a finalist for the 1990 Pulitzer Prize for Music and shared the top Kennedy Center Friedheim Award prize with William Kraft for Veils and Variations for Horn and Orchestra.[3][4]

In 1992 the Pulitzer Prize for Music jury, which that year consisted of George Perle, Roger Reynolds, and Harvey Sollberger, selected Shapey’s Concerto Fantastique for the award.[5] However, the Pulitzer Board rejected that decision and choose to give the prize to the jury’s second choice, Wayne Peterson‘s The Face of the Night, the Heart of the Dark. The music jury responded with a public statement stating that they had not been consulted in that decision and that the Board was not professionally qualified to make such a decision. The Board responded that the “Pulitzers are enhanced by having, in addition to the professional’s point of view, the layman’s or consumer’s point of view,” and they did not rescind their decision.[6][7]

Shapey created a body of over 200 works, many of which have been published by Presser. Presser also offers his textbook A Basic Course in Music Composition, written after over fifty years of teaching the subject. Recordings of Shapey’s music are available on the CRI, Opus One, and New World labels. Shapey’s works have been catalogued by Dr. Patrick D. Finley in A Catalogue of the Works of Ralph Shapey, published by Pendragon Press

His students include Gerald Levinson, Robert Carl, Gordon Marsh, Michael Eckert, Philip Fried, Matt Malsky, Lawrence Fritts, James Anthony Walker, Frank Retzel, Jorge Liderman, Jonathan Elliott, Terry Winter Owens, Deborah Drattell, Ursula Mamlok, Shulamit Ran, and Melinda Wagner, among others.[8] Shulamit Ran dedicated her Pulitzer Prize-winning Symphony to Shapey in 1990.