Scheide, William

William T. Scheide struck it rich in the Pennsylvania oil boom of the late 19th century and then surprised people by retiring at 42. For him, it was an easy decision. He had made more than enough money to do what he really wanted to do: buy books and read them.

William had a son, John, who shared his love for words. John carefully gave some of his money away — to his alma mater, Princeton, as well as to other colleges and to the Presbyterian Church — but he, too, spent most of his life reading and buying books, often rare ones. He built a library at his house in Titusville, Pa., with oak bookcases fronted by leaded glass doors and tables at which to sit and study.

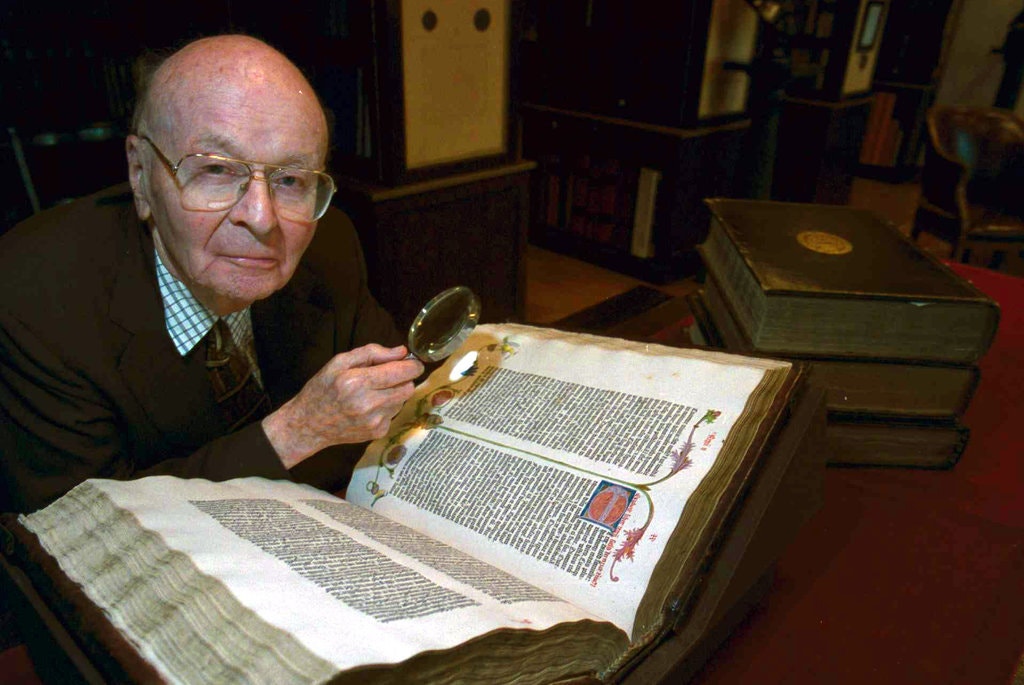

John’s son, William H. Scheide, grew up in a bedroom above the library. It was easy to go downstairs, pull up a chair and page through old texts — sections of the Bible on papyrus, a first folio of Shakespeare, a speech about slavery written in Lincoln’s hand. His interests became as diverse as the subjects on the shelves.

William Scheide was 28 when his father died and he inherited the family fortune. Over the next seven decades, he also passed down his passions, but to far more beneficiaries. Before his death on Nov. 14 at 100, Mr. Scheide devoted his life to philanthropic and artistic pursuits striking in their range and depth.

The library he explored as a boy is now the Scheide Library at Princeton, and his continuing acquisitions have made it one of the world’s finest collections of rare books. Mr. Scheide, who graduated from Princeton in 1936 (his father was in the class of 1896), moved the collection to the campus a half-century ago, paid for construction of a space to house it and made sure it would resemble the room he remembered by furnishing it with the same oak bookcases and tables.

Its holdings include the first four printed editions of the Bible, a 1776 first printing of the Declaration of Independence and the first book his grandfather bought, in September 1865, “The Chemical History of a Candle.”

Combing through Bach’s cantatas, Mr. Scheide had an idea. He wanted to extract their arias and duets, pieces mostly performed in worship services, and hear them performed in concert. In 1946, he put his research to work, founding the Bach Aria Group.

He hired accomplished musicians — including, over the years, the flutist Julius Baker, the oboist Robert Bloom, the cellist David Soyer and the soprano Eileen Farrell — and gave them long-term contracts. The group, which made its New York debut in 1948, became an acclaimed ensemble and released numerous recordings. It also drew criticism for playing the pieces out of their intended context.

“I think the private Bach is still private,” he said in an interview in 1980, the year he decided to end his financial involvement with the group. “A lot of it is still not well known by important musicians, and they’re missing quite a bit. I know the cantatas get done in churches, but I wanted to put them in the middle of our musical life.”

Not long after Mr. Scheide established the Bach Aria Group, he began developing a relationship few people knew of at the time: He became an essential financial supporter of some of the most important legal fights of the civil rights movement, and of the lawyer often leading them, the future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Mr. Scheide became active in local civil rights groups while living in Princeton in the early 1950s. When he received a mail solicitation from the Legal Defense Fund, he donated $5. But after Mr. Marshall got word of Mr. Scheide’s interest and his wealth, he asked him to help finance the landmark school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education.

The Legal Defense Fund said last week that Mr. Scheide had been its most generous individual donor and its longest-serving board member. (He joined in 1962.) His wife, Judith Scheide, also a member of the board, said in an interview on Friday that he had given the organization nearly $6 million in the last two decades.

William Hurd Scheide was born on Jan. 6, 1914, in Philadelphia, and grew up in Titusville. His mother, the former Harriet Hurd, was a social worker in New York when she met his father.

An only child, Mr. Scheide learned to play piano early and majored in history at Princeton only because the university did not offer a music major. Now it does, and Mr. Scheide has been generous to the music department as well as other parts of the university.