Rorem, Ned

Rorem was born in Richmond, Indiana on October 23, 1923. As a child he moved to Chicago with his family; by the age of ten his piano teacher had introduced him to Debussy and Ravel, an experience which “changed my life forever,” according to the composer. At seventeen he entered the Music School of Northwestern University, two years later receiving a scholarship to the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. He studied composition under Bernard Wagenaar at Juilliard, taking his B.A. in 1946 and his M.A. degree (along with the $1,000 George Gershwin Memorial Prize in composition) in 1948. In New York he worked as Virgil Thomson’s copyist in return for $20 a week and orchestration lessons. He studied on fellowship at the Berkshire Music Center in Tanglewood in the summers of 1946 and 1947; in 1948 his song The Lordly Hudson was voted the best published song of that year by the Music Library Association.

Words and music are inextricably linked for Ned Rorem. Time Magazine has called him “the world’s best composer of art songs,” yet his musical and literary ventures extend far beyond this specialized field. Rorem has composed three symphonies, four piano concertos and an array of other orchestral works, music for numerous combinations of chamber forces, six operas, choral works of every description, ballets and other music for the theater, and literally hundreds of songs and cycles. He is the author of thirteen books, including five volumes of diaries and collections of lectures and criticism.

In 1949 Rorem moved to France, and lived there until 1958. His years as a young composer among the leading figures of the artistic and social milieu of post-war Europe are absorbingly portrayed in The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem (Brazillier, 1966). He currently lives in New York City.

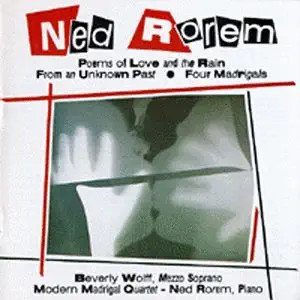

Ned Rorem has been the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship (1951), a Guggenheim Fellowship (1957), and an award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1968). He received the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award in 1971 for his book Critical Affairs, A Composer’s Journal, in 1975 for The Final Diary, and in 1992 for an article on American opera in Opera News. Among his many commissions for new works are those from the Ford Foundation (for Poems of Love and the Rain, 1962), the Lincoln Center Foundation (for Sun, 1965); the Koussevitzky Foundation (for Letters from Paris, 1966); the Atlanta Symphony (for the String Symphony, 1985); the Chicago Symphony (for Goodbye My Fancy, 1990); and from Carnegie Hall (for Spring Music, 1991). Among the distinguished conductors who have performed his music are Bernstein, Mitropoulos, Reiner, Ormandy, Steinberg, Stokowski, and Mehta; his suite Air Music won the 1976 Pulitzer Prize in music. The Atlanta Symphony recording of the String Symphony, Sunday Morning, and Eagles received a Grammy Award for Outstanding Orchestral Recording in 1989.

Celebrations of the composer’s 70th-birthday year began in February 1993 with the premiere of his Piano Concerto for Left Hand and Orchestra, which attracted international attention and critical plaudits; André Previn led soloist Gary Graffman and the Symphony Orchestra of the Curtis Institute of Music in performances at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia and Carnegie Hall in New York. In the months surrounding the birthday itself, all-Rorem concerts took place in New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Minneapolis, and Buffalo, along with major performances throughout the U.S., spanning the full range of his repertoire. In January 1994 Kurt Masur conducted English hornist Thomas Stacy and the New York Philharmonic in the first performances of Rorem’s Concerto for English Horn and Orchestra, commissioned by the orchestra in honor of its 150th anniversary season. Tour performances of the concerto have been scheduled by the Philharmonic for Leipzig, Dublin, Edinburgh, London (on the 1996 Proms), Copenhagen, and Lucerne.

Knowing When to Stop, Rorem’s newest book, is an autobiographical memoir of the composer’s first 28 years; issued by Simon and Schuster in fall 1994, it is now in its second printing and has come out in paperback. Rorem has said: “My music is a diary no less compromising than my prose. A diary nevertheless differs from a musical composition in that it depicts the moment, the writer’s present mood which, were it inscribed an hour later, could emerge quite otherwise. I don’t believe that composers notate their moods, they don’t tell the music where to go — it leads them….Why do I write music? Because I want to hear it — it’s simple as that. Others may have more talent, more sense of duty. But I compose just from necessity, and no one else is making what I need.”