Gottschalk, Louis Moreau

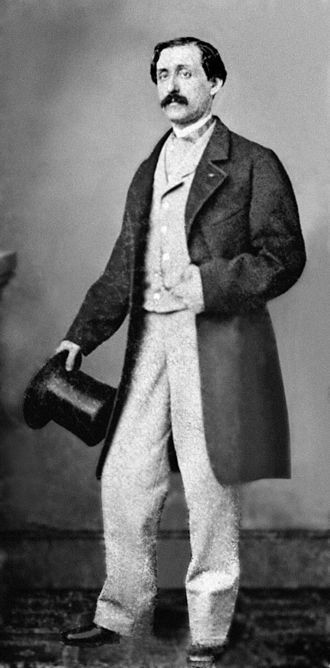

Louis Moreau Gottschalk (May 8, 1829 – December 18, 1869) was an American composer and pianist, best known as a virtuoso performer of his own romantic piano works.[1] He spent most of his working career outside of the United States.

Only two years later, at the age of 13, Gottschalk left the United States and sailed to Europe, as he and his father realized a classical training was required to fulfill his musical ambitions. The Paris Conservatoire, however, rejected his application without hearing him, on the grounds of his nationality; Pierre Zimmerman, head of the piano faculty, commented that “America is a country of steam engines”. Gottschalk eventually gained access to the musical establishment through family friends, but important early compositions like Bamboula (Danse Des Nègres) and La Savane establish him as a genuinely American composer, and not a mere copycat of the European written tradition; they were a major artistic statement as they carried a legacy of slave music in a romantic music context, and as such they were also precursors of jazz. They still stand as the first examples of Louisiana Creole music in classical music culture. After a concert at the Salle Pleyel, Frédéric Chopin remarked: “Give me your hand, my child; I predict that you will become the king of pianists.” Franz Liszt and Charles-Valentin Alkan, too, recognised Gottschalk’s extreme talent.[4]

After Gottschalk returned to the United States in 1853, he traveled extensively; a sojourn in Cuba during 1854 was the beginning of a series of trips to Central and South America.[5] Gottschalk also traveled to Puerto Rico after his Havana debut and at the start of his West Indian period. He was quite taken with the music he heard on the island, so much so that he composed a work, probably in 1857, entitled Souvenir de Porto Rico; Marche des gibaros, Op. 31 (RO250). “Gibaros” refers to the jíbaros, or Puerto Rican peasantry, and is an antiquated way of writing this name. The theme of the composition is a march tune which may be based on a Puerto Rican folk song form.[6]

At the conclusion of that tour, he rested in New Jersey then returned to New York City. There he continued to rest and took on a very young Venezuelan student, Teresa Carreño. Gottschalk rarely took on students and was skeptical of prodigies, but Carreño was an exception and he was determined that she succeed. With his busy schedule, Gottschalk was only able to give her a handful of lessons, yet she would remember him fondly and performed his music for the rest of her days. A year after meeting Gottschalk, she performed for Abraham Lincoln and would go on to become a renowned concert pianist earning the nickname “Valkyrie of the Piano”.

In late 1855 and early 1856 Gottschalk made connections with several notable figures of the New York art world, including the sculptor Erastus Dow Palmer, composer and musician George William Warren and Hudson River School landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church.[7] Like Gottschalk, Church had traveled extensively in Latin America (primarily Ecuador and Colombia) and produced a series of large-scale canvases of South American subject. Gottschalk dedicated a Mazurka poétique to Church, who gave Gottschalk a small (now unidentified) landscape painting.[8] Gottschalk also possibly collaborated with Warren on his 1863 The Andes, Marche di Bravoura, a solo piano piece inspired by Church’s large-scale South American painting of 1859, The Heart of the Andes.[9]

By the 1860s, Gottschalk had established himself as the best known pianist in the New World. Although born and reared in New Orleans, he was a supporter of the Union cause during the American Civil War. He returned to his native city only occasionally for concerts, but he always introduced himself as a New Orleans native. He composed the tarantella, Grande Tarantelle, Op. 67, subtitled Célèbre Tarentelle, during 1858–64.

In May 1865, he was mentioned in a San Francisco newspaper as having “travelled 95,000 miles by rail and given 1,000 concerts”. However, he was forced to leave the United States later that year because of a scandalous affair with a student at the Oakland Female Seminary in Oakland, California. He never returned to the United States.

Gottschalk chose to travel to South America, where he continued to give frequent concerts. During one of these concerts, at the Teatro Lyrico Fluminense in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on November 24, 1869, he collapsed from yellow fever.[10] Just before his collapse, he had finished playing his romantic piece Morte! (translated from Brazilian Portuguese as “Death”), although the actual collapse occurred just as he started to play his celebrated piece Tremolo. Gottschalk never recovered from the collapse.

Three weeks later, on December 18, 1869, at the age of 40, he died at his hotel in Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, probably from an overdose of quinine. (According to an essay by Jeremy Nicholas for the booklet accompanying the recording “Gottschalk Piano Music” performed by Philip Martin on the Hyperion label, “He died … of empyema, the result of a ruptured abscess in the abdomen.”)

In 1870, his remains were returned to the United States and were interred at the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.[11] His burial spot was originally marked by a magnificent marble monument, topped by an “Angel of Music” statue, which was irreparably damaged by vandals in 1959.[12] In October 2012, after nearly fifteen years of fundraising by the Green-Wood Cemetery, a new “Angel of Music” statue, created by sculptors Giancarlo Biagi and Jill Burkee to replace the damaged one, was unveiled.[13]

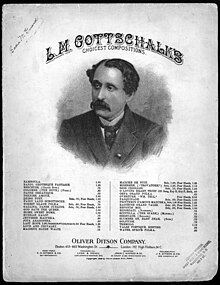

Louis Moreau Gottschalk pictured on an 1864 Publication of The Dying Poet for piano

Gottschalk’s music was very popular during his lifetime and his earliest compositions created a sensation in Europe. Early pieces like Bamboula, La Savane, Le Bananier and Le Mancenillier were based on Gottschalk’s memories of the music he heard during his youth in Louisiana and are widely regarded as the earliest existing pieces of creole music in classical culture. In this context, some of Gottschalk’s work, such as the 13-minute opera Escenas campestres, retains a wonderfully innocent sweetness and charm. Gottschalk also utilized the Bamboula theme as a melody in his Symphony No. 1: A Night in the Tropics.

Many of his compositions were destroyed after his death, or are lost.

Various pianists later recorded his piano music. The first important recordings of his orchestral music, including the symphony A Night in the Tropics, were made for Vanguard Records by Maurice Abravanel and the Utah Symphony Orchestra. Vox Records issued a multi-disc collection of his music, which was later reissued on CD. This included world premiere recordings of the original orchestrations of both symphonies and other works, which were conducted by Igor Buketoff and Samuel Adler. More recently, Philip Martin has recorded most of the extant piano music for Hyperion Records.

Author Howard Breslin wrote a historical novel about Gottschalk titled Concert Grand in 1963.[14] An interesting version of Gottschalk’s famous composition Bamboula with added lyrics was recorded in April 1934 by trumpet player Abel Beauregard’s dance band, the Orchestre Créole Matou from the French Caribbean Guadeloupe island.[15] It is actually the first recording in existence of this composition, as the first ‘classical piano’ recordings of Gottschalk’s works were made in 1956 by American pianist Eugene List.[16] Other recordings related to the specific bamboula rhythm heard by Gottschalk in New Orleans’ Congo Square and used on his famous 1845 composition Bamboula can be found on a 1950 Haitian voodoo recording Baboule Dance (three drums);[17] And on the 1962 Cuban folk tune Rezos Congos (Bamboula, Conga Music).[18] Comments by musicologist Bruno Blum are included in each of the above releases. New Orleans singer and pianist Dr. John‘s recording of Litanie des Saints from Goin’ Back to New Orleans was inspired by Gottschalk’s Souvenir de Porto Rico.[19]