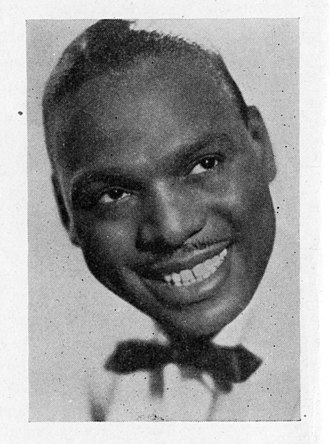

Hines, Earl "Fatha"

Earl Kenneth Hines, also known as Earl “Fatha” Hines (December 28, 1903– April 22, 1983), was an American jazz pianist and bandleader. He was one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano and, according to one source, “one of a small number of pianists whose playing shaped the history of jazz”.

The trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (a member of Hines’s big band, along with Charlie Parker) wrote, “The piano is the basis of modern harmony. This little guy came out of Chicago, Earl Hines. He changed the style of the piano. You can find the roots of Bud Powell, Herbie Hancock, all the guys who came after that. If it hadn’t been for Earl Hines blazing the path for the next generation to come, it’s no telling where or how they would be playing now. There were individual variations but the style of … the modern piano came from Earl Hines.”

The pianist Lennie Tristano said, “Earl Hines is the only one of us capable of creating real jazz and real swing when playing all alone.” Horace Silver said, “He has a completely unique style. No one can get that sound, no other pianist”. Erroll Garner said, “When you talk about greatness, you talk about Art Tatum and Earl Hines”.

Count Basie said that Hines was “the greatest piano player in the world”.

Hines met Louis Armstrong in the poolroom of the Black Musicians’ Union, local 208, on State and 39th in Chicago.[10] Hines was 21, Armstrong 24. They played the union’s piano together. Armstrong was astounded by Hines’s avant-garde “trumpet-style” piano playing, often using dazzlingly fast octaves so that on none-too-perfect upright pianos (and with no amplification) “they could hear me out front”. Richard Cook wrote in Jazz Encyclopedia that

[Hines’s] most dramatic departure from what other pianists were then playing was his approach to the underlying pulse: he would charge against the metre of the piece being played, accent off-beats, introduce sudden stops and brief silences. In other hands this might sound clumsy or all over the place but Hines could keep his bearings with uncanny resilience.

Armstrong and Hines became good friends and shared a car. Armstrong joined Hines in Carroll Dickerson‘s band at the Sunset Cafe. In 1927, this became Armstrong’s band under the musical direction of Hines. Later that year, Armstrong revamped his Okeh Records recording-only band, Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five, and hired Hines as the pianist, replacing his wife, Lil Hardin Armstrong, on the instrument.

Armstrong and Hines then recorded what are often regarded as some of the most important jazz records ever made.

… with Earl Hines arriving on piano, Armstrong was already approaching the stature of a concerto soloist, a role he would play more or less throughout the next decade, which makes these final small-group sessions something like a reluctant farewell to jazz’s first golden age. Since Hines is also magnificent on these discs (and their insouciant exuberance is a marvel on the duet showstopper “Weather Bird“) the results seem like eavesdropping on great men speaking almost quietly among themselves. There is nothing in jazz finer or more moving than the playing on “West End Blues“, “Tight Like This”, “Beau Koo Jack” and “Muggles”.

In the days of 78s, recording engineers were unable to play back a take without rendering the wax master unusable for commercial release, so the band did not hear the final version of “West End Blues” until it was issued by OKeh a few weeks later. “Earl Hines, he was surprised when the record came out on the market, ’cause he brought it by my house, you know, we’d forgotten we’d recorded it”, Armstrong recalled in 1956. But they liked what they heard. “When it first came out”, Hines said, “Louis and I stayed by that recording practically an hour and a half or two hours and we just knocked each other out because we had no idea it was gonna turn out as good as it did.”

The Sunset Cafe closed in 1927. Hines, Armstrong and the drummer Zutty Singleton agreed that they would become the “Unholy Three” – they would “stick together and not play for anyone unless the three of us were hired”. But as Louis Armstrong and His Stompers (with Hines as musical director), they ran into difficulties trying to establish their own venue, the Warwick Hall Club, which they rented for a year with the management help of Lil Hardin Armstrong. Hines went briefly to New York and returned to find that Armstrong and Singleton had rejoined the rival Dickerson band at the new Savoy Ballroom in his absence, leaving Hines feeling “warm”. When Armstrong and Singleton later asked him to join them with Dickerson at the Savoy Ballroom, Hines said, “No, you guys left me in the rain and broke the little corporation we had”.

Hines joined the clarinetist Jimmie Noone at the Apex, an after-hours speakeasy, playing from midnight to 6 a.m., seven nights a week. In 1928, he recorded 14 sides with Noone and again with Armstrong (for a total of 38 sides with Armstrong). His first piano solos were recorded late that year: eight for QRS Records in New York and then seven for Okeh Records in Chicago, all except two his own compositions.

Hines moved in with Kathryn Perry (with whom he had recorded “Sadie Green the Vamp of New Orleans”). Hines said of her, “She’d been at The Sunset too, in a dance act. She was a very charming, pretty girl. She had a good voice and played the violin. I had been divorced and she became my common-law wife. We lived in a big apartment and her parents stayed with us”. Perry recorded several times with Hines, including “Body & Soul” in 1935. They stayed together until 1940, when Hines “divorced” her to marry Ann Jones Reed, but that marriage was soon “indefinitely postponed”.

Hines married singer ‘Lady of Song’ Janie Moses in 1947. They had two daughters, Janear (born 1950) and Tosca. Both daughters died before he did, Tosca in 1976 and Janear in 1981. Janie divorced him on June 14, 1979 and died in 2007.

In 1942, Hines provided the saxophonist Charlie Parker with his big break, although Parker was subsequently fired soon after for his “time-keeping” – by which Hines meant his inability to show up on time – despite Parker resorting to sleeping under the band stage in his attempts to be punctual. Dizzie Gillespie joined the same year.

The Grand Terrace Cafe had closed suddenly in December 1940; its manager, the cigar-puffing Ed Fox, disappeared. The 37-year-old Hines, always famously good to work for, took his band on the road full-time for the next eight years, resisting renewed offers from Benny Goodman to join his band as piano player.

Several members of Hines’s band were drafted into the armed forces in World War II – a major problem. Six were drafted in 1943 alone. As a result, on August 19, 1943, Hines had to cancel the rest of his Southern tour. He went to New York and hired a “draft-proof” 12-piece all-woman group, which lasted two months. Next, Hines expanded it into a 28-piece band (17 men, 11 women), including strings and French horn. Despite these wartime difficulties, Hines took his bands on tour from coast to coast but was still able to take time out from his own band to front the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1944 when Ellington fell ill.

It was during this time (and especially during the recording ban during the 1942–44 musicians’ strike ) that late-night jam sessions with members of Hines’s band’s sowed the seeds for the emerging new style in jazz, bebop. Ellington later said that “the seeds of bop were in Earl Hines’s piano style”. Charlie Parker’s biographer Ross Russell wrote:

The Earl Hines Orchestra of 1942 had been infiltrated by the jazz revolutionaries. Each section had its cell of insurgents. The band’s sonority bristled with flatted fifths, off triplets and other material of the new sound scheme. Fellow bandleaders of a more conservative bent warned Hines that he had recruited much too well and was sitting on a powder keg.

As early as 1940, saxophone player and arranger Budd Johnson had “re-written the book” for the Hines’ band in a more modern style. Johnson and Billy Eckstine, Hines vocalist between 1939 and 1943, have been credited with helping to bring modern players into the Hines band in the transition between swing and bebop. Apart from Parker and Gillespie, other Hines ‘modernists’ included Gene Ammons, Gail Brockman, Scoops Carry, Goon Gardner, Wardell Gray, Bennie Green, Benny Harris, Harry ‘Pee-Wee’ Jackson, Shorty McConnell, Cliff Smalls, Shadow Wilson and Sarah Vaughan, who replaced Eckstine as the band singer in 1943 and stayed for a year.

Dizzy Gillespie said of the music the band evolved:

People talk about the Hines band being ‘the incubator of bop’ and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here … naturally each age has got its own shit.

The links to bebop remained close. Parker’s discographer, among others, has argued that “Yardbird Suite“, which Parker recorded with Miles Davis in March 1946, was in fact based on Hines’ “Rosetta”, which nightly served as the Hines band theme-tune.

Dizzy Gillespie described the Hines band, saying, “We had a beautiful, beautiful band with Earl Hines. He’s a master and you learn a lot from him, self-discipline and organization.”

In July 1946, Hines suffered serious head injuries in a car crash near Houston which, despite an operation, affected his eyesight for the rest of his life. Back on the road again four months later, he continued to lead his big band for two more years. In 1947, Hines bought the biggest nightclub in Chicago, The El Grotto, but it soon foundered with Hines losing $30,000 ($398,140 today). The big-band era was over – Hines’ bands had been at the top for 20 years.

In early 1948, Hines joined up again with Armstrong in the “Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars” “small-band”. It was not without its strains for Hines. A year later, Armstrong became the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of Time magazine (on February 21, 1949). Armstrong was by then on his way to becoming an American icon, leaving Hines to feel he was being used only as a sideman in comparison to his old friend. Armstrong said of the difficulties, mainly over billing, “Hines and his ego, ego, ego …”, but after three years and to Armstrong’s annoyance, Hines left the All Stars in 1951.

Next, back as leader again, Hines took his own small combos around the United States. He started with a markedly more modern lineup than the aging All Stars: Bennie Green, Art Blakey, Tommy Potter, and Etta Jones. In 1954, he toured his then seven-piece group nationwide with the Harlem Globetrotters. In 1958 he broadcast on the American Forces Network but by the start of the jazz-lean 1960s and old enough to retire, Hines settled “home” in Oakland, California, with his wife and two young daughters, opened a tobacconist’s, and came close to giving up the profession.

Then, in 1964, thanks to Stanley Dance, his determined friend and unofficial manager, Hines was “suddenly rediscovered” following a series of recitals at the Little Theatre in New York, which Dance had cajoled him into. They were the first piano recitals Hines had ever given; they caused a sensation. “What is there left to hear after you’ve heard Earl Hines?”, asked John Wilson of The New York Times. Hines then won the 1966 International Critics Poll for Down Beat magazine’s Hall of Fame. Down Beat also elected him the world’s “No. 1 Jazz Pianist” in 1966 (and did so again five more times). Jazz Journal awarded his LPs of the year first and second in its overall poll and first, second and third in its piano category. Jazz voted him “Jazzman of the Year” and picked him for its number 1 and number 2 places in the category Piano Recordings. Hines was invited to appear on TV shows hosted by Johnny Carson and Mike Douglas.

But the most highly regarded recordings of this period are his solo performances, “a whole orchestra by himself”. Whitney Balliett wrote of his solo recordings and performances of this time:

Hines will be sixty-seven this year and his style has become involuted, rococo, and subtle to the point of elusiveness. It unfolds in orchestral layers and it demands intense listening. Despite the sheer mass of notes he now uses, his playing is never fatty. Hines may go along like this in a medium tempo blues. He will play the first two choruses softly and out of tempo, unreeling placid chords that safely hold the kernel of the melody. By the third chorus, he will have slid into a steady but implied beat and raised his volume. Then, using steady tenths in his left hand, he will stamp out a whole chorus of right-hand chords in between beats. He will vault into the upper register in the next chorus and wind through irregularly placed notes, while his left hand plays descending, on-the-beat, chords that pass through a forest of harmonic changes. (There are so many push-me, pull-you contrasts going on in such a chorus that it is impossible to grasp it one time through.) In the next chorus—bang!—up goes the volume again and Hines breaks into a crazy-legged double-time-and-a-half run that may make several sweeps up and down the keyboard and that are punctuated by offbeat single notes in the left hand. Then he will throw in several fast descending two-fingered glissandos, go abruptly into an arrhythmic swirl of chords and short, broken, runs and, as abruptly as he began it all, ease into an interlude of relaxed chords and poling single notes. But these choruses, which may be followed by eight or ten more before Hines has finished what he has to say, are irresistible in other ways. Each is a complete creation in itself, and yet each is lashed tightly to the next.

Solo tributes to Armstrong, Hoagy Carmichael, Ellington, George Gershwin and Cole Porter were all put on record in the 1970s, sometimes on the 1904 12-legged Steinway given to him in 1969 by Scott Newhall, the managing editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1974, when he was in his seventies, Hines recorded sixteen LPs. “A spate of solo recording meant that, in his old age, Hines was being comprehensively documented at last, and he rose to the challenge with consistent inspirational force”. From his 1964 “comeback” until his death, Hines recorded over 100 LPs all over the world. Within the industry, he became legendary for going into a studio and coming out an hour and a half later having recorded an unplanned solo LP. Retakes were almost unheard of except when Hines wanted to try a tune again in some other way, often completely different.

From 1964 on, Hines often toured Europe, especially France. He toured South America in 1968. He performed in Asia, Australia, Japan and, in 1966, the Soviet Union, in tours funded by the U.S. State Department. During his six-week tour of the Soviet Union, in which he performed 35 concerts, the 10,000-seat Kyiv Sports Palace was sold out. As a result, the Kremlin cancelled his Moscow and Leningrad concerts as being “too culturally dangerous”.

Arguably still playing as well as he ever had, Hines displayed individualistic quirks (including grunts) in these performances. He sometimes sang as he played, especially his own “They Didn’t Believe I Could Do It … Neither Did I”. In 1975, Hines was the subject of an hour-long television documentary film made by ATV (for Britain’s commercial ITV channel), out-of-hours at the Blues Alley nightclub in Washington, DC. The International Herald Tribune described it as “the greatest jazz film ever made”. In the film, Hines said, “The way I like to play is that … I’m an explorer, if I might use that expression, I’m looking for something all the time … almost like I’m trying to talk.” In 1979, Hines was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame. He played solo at Duke Ellington’s funeral, played solo twice at the White House, for the President of France and for the Pope. Of this acclaim, Hines said, “Usually they give people credit when they’re dead. I got my flowers while I was living”

Hines’s last show took place in San Francisco a few days before he died of a heart attack in Oakland. As he had wished, his Steinway was auctioned for the benefit of gifted low-income music students, still bearing its silver plaque:

- presented by jazz lovers from all over the world. this piano is the only one of its kind in the world and expresses the great genius of a man who has never played a melancholy note in his lifetime on a planet that has often succumbed to despair.

Hines was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California.