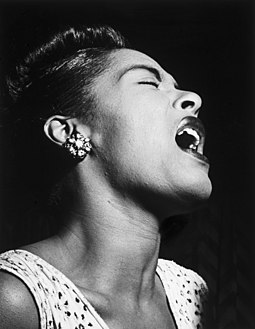

Holiday, Billie

Eleanora Fagan (April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959), known professionally as Billie Holiday, was an American jazz and swing music singer. Nicknamed “Lady Day” by her friend and music partner Lester Young, Holiday had an innovative influence on jazz music and pop singing. Her vocal style, strongly inspired by jazz instrumentalists, pioneered a new way of manipulating phrasing and tempo. She was known for her vocal delivery and improvisational skills.

After a turbulent childhood, Holiday began singing in nightclubs in Harlem, where she was heard by producer John Hammond, who liked her voice. She signed a recording contract with Brunswick in 1935. Collaborations with Teddy Wilson produced the hit “What a Little Moonlight Can Do”, which became a jazz standard. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Holiday had mainstream success on labels such as Columbia and Decca. By the late 1940s, however, she was beset with legal troubles and drug abuse. After a short prison sentence, she performed at a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall. She was a successful concert performer throughout the 1950s with two further sold-out shows at Carnegie Hall. Because of personal struggles and an altered voice, her final recordings were met with mixed reaction but were mild commercial successes. Her final album, Lady in Satin, was released in 1958. Holiday died of cirrhosis on July 17, 1959, at age 44.

Holiday won four Grammy Awards, all of them posthumously, for Best Historical Album. She was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame and the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame. She was also inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, though not in that genre; the website states that “Billie Holiday changed jazz forever”. Several films about her life have been released, most recently The United States vs. Billie Holiday

As a young teenager, Holiday started singing in nightclubs in Harlem. She took her professional pseudonym from Billie Dove, an actress she admired, and Clarence Halliday, her probable father. At the outset of her career, she spelled her last name “Halliday”, her father’s birth surname, but eventually changed it to “Holiday”, his performing name. The young singer teamed up with a neighbor, tenor saxophone player Kenneth Hollan. They were a team from 1929 to 1931, performing at clubs such as the Grey Dawn, Pod’s and Jerry’s on 133rd Street, and the Brooklyn Elks’ Club.[19][20] Benny Goodman recalled hearing Holiday in 1931 at the Bright Spot. As her reputation grew, she played in many clubs, including the Mexico’s and the Alhambra Bar and Grill, where she met Charles Linton, a vocalist who later worked with Chick Webb. It was also during this period that she connected with her father, who was playing in Fletcher Henderson‘s band.

Late in 1932, 17-year-old Holiday replaced the singer Monette Moore at Covan’s, a club on West 132nd Street. Producer John Hammond, who loved Moore’s singing and had come to hear her, first heard Holiday there in early 1933. Hammond arranged for Holiday to make her recording debut at age 18, in November 1933, with Benny Goodman. She recorded two songs: “Your Mother’s Son-In-Law” and “Riffin’ the Scotch”, the latter being her first hit. “Son-in-Law” sold 300 copies, and “Riffin’ the Scotch”, released on November 11, sold 5,000 copies. Hammond was impressed by Holiday’s singing style and said of her, “Her singing almost changed my music tastes and my musical life, because she was the first girl singer I’d come across who actually sang like an improvising jazz genius.” Hammond compared Holiday favorably to Armstrong and said she had a good sense of lyric content at her young age.

In 1935, Holiday had a small role as a woman abused by her lover in Duke Ellington‘s musical short film Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life. She sang “Saddest Tale” in her scene.

In 1935, Holiday was signed to Brunswick by John Hammond to record pop tunes with pianist Teddy Wilson in the swing style for the growing jukebox trade. They were allowed to improvise on the material. Holiday’s improvisation of melody to fit the emotion was revolutionary. Their first collaboration included “What a Little Moonlight Can Do” and “Miss Brown to You“. “What a Little Moonlight Can Do” has been deemed her “claim to fame”.[25] Brunswick did not favor the recording session because producers wanted Holiday to sound more like Cleo Brown. However, after “What a Little Moonlight Can Do” was successful, the company began considering Holiday an artist in her own right. She began recording under her own name a year later for Vocalion in sessions produced by Hammond and Bernie Hanighen. Hammond said the Wilson-Holiday records from 1935 to 1938 were a great asset to Brunswick. According to Hammond, Brunswick was broke and unable to record many jazz tunes. Wilson, Holiday, Young, and other musicians came into the studio without written arrangements, reducing the recording cost. Brunswick paid Holiday a flat fee rather than royalties, which saved the company money. “I Cried for You” sold 15,000 copies, which Hammond called “a giant hit for Brunswick…. Most records that made money sold around three to four thousand.”

Another frequent accompanist was tenor saxophonist Lester Young, who had been a boarder at her mother’s house in 1934 and with whom Holiday had a rapport. Young said, “I think you can hear that on some of the old records, you know. Some time I’d sit down and listen to ’em myself, and it sound like two of the same voices … or the same mind, or something like that.” Young nicknamed her “Lady Day”, and she called him “Prez”.

In late 1937, Holiday had a brief stint as a big-band vocalist with Count Basie. The traveling conditions of the band were often poor; they performed many one-nighters in clubs, moving from city to city with little stability. Holiday chose the songs she sang and had a hand in the arrangements, choosing to portray her developing persona of a woman unlucky in love. Her tunes included “I Must Have That Man”, “Travelin’ All Alone”, “I Can’t Get Started“, and “Summertime“, a hit for Holiday in 1936, originating in George Gershwin‘s Porgy and Bess the year before. Basie became used to Holiday’s heavy involvement in the band. He said, “When she rehearsed with the band, it was really just a matter of getting her tunes like she wanted them, because she knew how she wanted to sound and you couldn’t tell her what to do.” Some of the songs Holiday performed with Basie were recorded. “I Can’t Get Started”, “They Can’t Take That Away from Me“, and “Swing It Brother Swing” are all commercially available. Holiday was unable to record in the studio with Basie, but she included many of his musicians in her recording sessions with Teddy Wilson.

Holiday found herself in direct competition with the popular singer Ella Fitzgerald. The two later became friends. Fitzgerald was the vocalist for the Chick Webb Band, which was in competition with the Basie band. On January 16, 1938, the same day that Benny Goodman performed his legendary Carnegie Hall jazz concert, the Basie and Webb bands had a battle at the Savoy Ballroom. Webb and Fitzgerald were declared winners by Metronome magazine, while DownBeat magazine pronounced Holiday and Basie the winners. Fitzgerald won a straw poll of the audience by a three-to-one margin.

By February 1938, Holiday was no longer singing for Basie. Various reasons have been given for why she was fired. Jimmy Rushing, Basie’s male vocalist, called her unprofessional. According to All Music Guide, Holiday was fired for being “temperamental and unreliable”. She complained of low pay and poor working conditions and may have refused to sing the songs requested of her or change her style. Holiday was hired by Artie Shaw a month after being fired from the Count Basie Band. This association placed her among the first black women to work with a white orchestra, an unusual arrangement at that time. This was also the first time a black female singer employed full-time toured the segregated U.S. South with a white bandleader. In situations where there was a lot of racial tension, Shaw was known to stick up for his vocalist. In her autobiography, Holiday describes an incident in which she was not permitted to sit on the bandstand with other vocalists because she was black. Shaw said to her, “I want you on the band stand like Helen Forrest, Tony Pastor and everyone else.” When touring the South, Holiday would sometimes be heckled by members of the audience. In Louisville, Kentucky, a man called her a “nigger wench” and requested she sing another song. Holiday lost her temper and had to be escorted off the stage.

By March 1938, Shaw and Holiday had been broadcast on New York City’s powerful radio station WABC (the original WABC, now WCBS). Because of their success, they were given an extra time slot to broadcast in April, which increased their exposure. The New York Amsterdam News reviewed the broadcasts and reported an improvement in Holiday’s performance. Metronome reported that the addition of Holiday to Shaw’s band put it in the “top brackets”. Holiday could not sing as often during Shaw’s shows as she could in Basie’s; the repertoire was more instrumental, with fewer vocals. Shaw was also pressured to hire a white singer, Nita Bradley, with whom Holiday did not get along but had to share a bandstand. In May 1938, Shaw won band battles against Tommy Dorsey and Red Norvo, with the audience favoring Holiday. Although Shaw admired Holiday’s singing in his band, saying she had a “remarkable ear” and a “remarkable sense of time”, her tenure with the band was nearing an end. In November 1938, Holiday was asked to use the service elevator at the Lincoln Hotel, instead of the passenger elevator, because white patrons of the hotels complained. This may have been the last straw for her. She left the band shortly after. Holiday spoke about the incident weeks later, saying, “I was never allowed to visit the bar or the dining room as did other members of the band … [and] I was made to leave and enter through the kitchen.” There are no surviving live recordings of Holiday with Shaw’s band. Because she was under contract to a different record label and possibly because of her race, Holiday was able to make only one record with Shaw, “Any Old Time”. However, Shaw played clarinet on four songs she recorded in New York on July 10, 1936: “Did I Remember?”, “No Regrets”, “Summertime” and “Billie’s Blues“.

By the late 1930s, Holiday had toured with Count Basie and Artie Shaw, scored a string of radio and retail hits with Teddy Wilson, and became an established artist in the recording industry. Her songs “What a Little Moonlight Can Do” and “Easy Living” were imitated by singers across America and were quickly becoming jazz standards. In September 1938, Holiday’s single “I’m Gonna Lock My Heart” ranked sixth as the most-played song that month. Her record label, Vocalion, listed the single as its fourth-best seller for the same month, and it peaked at number 2 on the pop charts, according to Joel Whitburn’s Pop Memories: 1890–1954.

Holiday was in the middle of recording for Columbia in the late 1930s when she was introduced to “Strange Fruit“, a song based on a poem about lynching written by Abel Meeropol, a Jewish schoolteacher from the Bronx. Meeropol used the pseudonym “Lewis Allan” for the poem, which was set to music and performed at teachers’ union meetings. It was eventually heard by Barney Josephson, the proprietor of Café Society, an integrated nightclub in Greenwich Village, who introduced it to Holiday. She performed it at the club in 1939, with some trepidation, fearing possible retaliation. She later said that the imagery of the song reminded her of her father’s death and that this played a role in her resistance to performing it.

For her performance of “Strange Fruit” at the Café Society, she had waiters silence the crowd when the song began. During the song’s long introduction, the lights dimmed and all movement had to cease. As Holiday began singing, only a small spotlight illuminated her face. On the final note, all lights went out, and when they came back on, Holiday was gone. Holiday said her father, Clarence Holiday, was denied medical treatment for a fatal lung disorder because of racial prejudice, and that singing “Strange Fruit” reminded her of the incident. “It reminds me of how Pop died, but I have to keep singing it, not only because people ask for it, but because twenty years after Pop died the things that killed him are still happening in the South”, she wrote in her autobiography. When Holiday’s producers at Columbia found the subject matter too sensitive, Milt Gabler agreed to record it for his Commodore Records label on April 20, 1939. “Strange Fruit” remained in her repertoire for 20 years. She recorded it again for Verve. The Commodore release did not get any airplay, but the controversial song sold well, though Gabler attributed that mostly to the record’s other side, “Fine and Mellow“, which was a jukebox hit.“The version I recorded for Commodore”, Holiday said of “Strange Fruit”, “became my biggest-selling record.” “Strange Fruit” was the equivalent of a top-twenty hit in the 1930s.

Holiday’s popularity increased after “Strange Fruit”. She received a mention in Time magazine. “I open Café Society as an unknown”, Holiday said. “I left two years later as a star. I needed the prestige and publicity all right, but you can’t pay rent with it.” She soon demanded a raise from her manager, Joe Glaser. Holiday returned to Commodore in 1944, recording songs she made with Teddy Wilson in the 1930s, including “I Cover the Waterfront“, “I’ll Get By“, and “He’s Funny That Way“. She also recorded new songs that were popular at the time, including, “My Old Flame“, “How Am I to Know?”, “I’m Yours”, and “I’ll Be Seeing You“, a number one hit for Bing Crosby. She also recorded her version of “Embraceable You“, which was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2005.

By 1947, Holiday was at her commercial peak, having made $250,000 in the three previous years. She was ranked second in the DownBeat poll for 1946 and 1947, her highest ranking in that poll. She was ranked fifth in Billboard ‘s annual college poll of “girl singers” on July 6, 1947 (Jo Stafford was first). In 1946, Holiday won the Metronome magazine popularity poll.

Ed Fishman (who fought with Joe Glaser to be Holiday’s manager) thought of a comeback concert at Carnegie Hall. Holiday hesitated, unsure audiences would accept her after the arrest. She gave in and agreed to appear. On March 27, 1948, Holiday played Carnegie Hall to a sold-out crowd. 2,700 tickets were sold in advance, a record at the time for the venue. Her popularity was unusual because she didn’t have a current hit record. Her last record to reach the charts was “Lover Man” in 1945. Holiday sang 32 songs at the Carnegie concert by her count, including Cole Porter‘s “Night and Day” and her 1930s hit, “Strange Fruit”. During the show, someone sent her a box of gardenias. “My old trademark”, Holiday said. “I took them out of box and fastened them smack to the side of my head without even looking twice.” There was a hatpin in the gardenias and Holiday unknowingly stuck it into the side of her head. “I didn’t feel anything until the blood started rushing down in my eyes and ears”, she said. After the third curtain call, she passed out.

On April 27, 1948, Bob Sylvester and her promoter Al Wilde arranged a Broadway show for her. Titled Holiday on Broadway, it sold out. “The regular music critics and drama critics came and treated us like we were legit”, she said. But it closed after three weeks.

Holiday was arrested again on January 22, 1949, in her room at the Hotel Mark Twain in San Francisco. Holiday said she began using hard drugs in the early 1940s. She married trombonist Jimmy Monroe on August 25, 1941. While still married, she became involved with trumpeter Joe Guy, her drug dealer. She divorced Monroe in 1947 and also split with Guy.

The loss of her cabaret card reduced Holiday’s earnings. She had not received proper record royalties until she joined Decca, so her main revenue was club concerts. The problem worsened when Holiday’s records went out of print in the 1950s. She seldom received royalties in her later years. In 1958, she received a royalty of only $11. Her lawyer in the late 1950s, Earle Warren Zaidins, registered with BMI only two songs she had written or co-written, costing her revenue. In 1948, Holiday played at the Ebony Club, which was against the law. Her manager, John Levy, was convinced he could get her card back and allowed her to open without one. “I opened scared”, Holiday said, “[I was] expecting the cops to come in any chorus and carry me off. But nothing happened. I was a huge success.”

Holiday recorded Gershwin’s “I Loves You, Porgy” in 1948. In 1950, Holiday appeared in the Universal short film Sugar Chile Robinson, Billie Holiday, Count Basie and His Sextet, singing “God Bless the Child” and “Now, Baby or Never”.

Holiday’s autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, was ghostwritten by William Dufty and published in 1956. Dufty, a New York Post writer and editor then married to Holiday’s close friend Maely Dufty, wrote the book quickly from a series of conversations with the singer in the Duftys’ 93rd Street apartment. He also drew on the work of earlier interviewers and intended to let Holiday tell her story in her own way. In his 2015 study, Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth, John Szwed argued that Lady Sings the Blues is a generally accurate account of her life, but that co-writer Dufty was forced to water down or suppress material by the threat of legal action. According to the reviewer Richard Brody, “Szwed traces the stories of two important relationships that are missing from the book—with Charles Laughton, in the 1930s, and with Tallulah Bankhead, in the late 1940s—and of one relationship that’s sharply diminished in the book, her affair with Orson Welles around the time of Citizen Kane.”[87] To accompany her autobiography, Holiday released the LP Lady Sings the Blues in June 1956. The album featured four new tracks, “Lady Sings the Blues“, “Too Marvelous for Words“, “Willow Weep for Me“, and “I Thought About You“, and eight new recordings of her biggest hits to date. The re-recordings included “Trav’lin’ Light” “Strange Fruit” and “God Bless the Child”. A review of the album was published by Billboard magazine on December 22, 1956, calling it a worthy musical complement to her autobiography. “Holiday is in good voice now”, wrote the reviewer, “and these new readings will be much appreciated by her following”. “Strange Fruit” and “God Bless the Child” were called classics, and “Good Morning Heartache”, another reissued track on the LP, was also noted favorably.

Her performance of “Fine and Mellow” on CBS‘s The Sound of Jazz program is memorable for her interplay with her long-time friend Lester Young. Both were less than two years from death. Young died in March 1959. Holiday wanted to sing at his funeral, but her request was denied.

When Holiday returned to Europe almost five years later, in 1959, she made one of her last television appearances for Granada’s Chelsea at Nine in London. Her final studio recordings were made for MGM Records in 1959, with lush backing from Ray Ellis and his Orchestra, who had also accompanied her on the Columbia album Lady in Satin the previous year. The MGM sessions were released posthumously on a self-titled album, later retitled and re-released as Last Recording.

On March 28, 1957, Holiday married Louis McKay, a mob enforcer. McKay, like most of the men in her life, was abusive. They were separated at the time of her death, but McKay had plans to start a chain of Billie Holiday vocal studios, on the model of the Arthur Murray dance schools. Holiday was childless, but she had two godchildren: singer Billie Lorraine Feather (the daughter of Leonard Feather) and Bevan Dufty (the son of William Dufty)

By early 1959, Holiday was diagnosed with cirrhosis. Although she had initially stopped drinking on her doctor’s orders, it was not long before she relapsed. By May 1959, she had lost 20 pounds (9.1 kg). Her manager Joe Glaser, jazz critic Leonard Feather, photojournalist Allan Morrison, and the singer’s own friends all tried in vain to persuade her to go to a hospital. On May 31, 1959, Holiday was taken to Metropolitan Hospital in New York for treatment of liver disease and heart disease. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics, under the order of the openly racist Harry J. Anslinger, had been targeting Holiday since at least 1939, when she started to perform “Strange Fruit“. She was arrested and handcuffed for drug possession. As she lay dying, her hospital room was raided, and she was placed under police guard. On July 15, she received the last rites of the Roman Catholic Church. She died at age 44, at 3:10 a.m. on July 17, of pulmonary edema and heart failure caused by cirrhosis of the liver.