Roussel, Albert

Albert Charles Paul Marie Roussel (5 April 1869 – 23 August 1937) was a French composer. He spent seven years as a midshipman, turned to music as an adult, and became one of the most prominent French composers of the interwar period. His early works were strongly influenced by the impressionism of Debussy and Ravel, while he later turned toward neoclassicism.

Born in Tourcoing (Nord), Roussel’s earliest interest was not in music but mathematics. He spent time in the French Navy, and in 1889 and 1890, he served on the crew of the frigate Iphigénie and spent several years in southern Vietnam.[1] These travels affected him artistically, as many of his musical works would reflect his interest in far-off, exotic places.

After resigning from the Navy in 1894, he began to study harmony in Roubaix, first with Julien Koszul (grandfather of composer Henri Dutilleux), who encouraged him to pursue his formation in Paris with Eugène Gigout, then continued his studies until 1908 at the Schola Cantorum de Paris where one of his teachers was Vincent d’Indy. While studying, he also taught. His students included Erik Satie and Edgard Varèse.

During World War I, he served as an ambulance driver on the Western Front. Following the war, he bought a summer house in Normandy and devoted most of his time there to composition.

Starting in 1923, another of Roussel’s students was Bohuslav Martinů, who dedicated his Serenade for Chamber Orchestra (1930) to Roussel.[2]

His sixtieth birthday was marked by a series of three concerts of his works in Paris that also included the performance of a collection of piano pieces, Homage to Albert Roussel, written by several composers, including Ibert, Poulenc, and Honegger.[1][3]

Roussel died in the village (commune) of Royan (Charente-Maritime), in western France, in 1937, and was buried in the churchyard of Saint Valery in Varengeville-sur-Mer (Normandy).

By temperament Roussel was predominantly a classicist. While his early work was strongly influenced by impressionism in music, he eventually arrived at a personal style which was more formal in design, with a strong rhythmic drive, and with a more distinct affinity for functional tonality than is found in the work of his more famous contemporaries Debussy, Ravel, Satie, and Stravinsky.

Roussel’s training at the Schola Cantorum, with its emphasis on rigorous academic models such as Palestrina and Bach, left its mark on his mature style, which is characterized by contrapuntal textures. On the whole Roussel’s orchestration is rather heavy compared to the subtle and nuanced style of other French composers like Debussy or, indeed, Gabriel Fauré. He preserved something of the romantic aesthetic in his orchestral works, and this sets him apart from Stravinsky and Les Six.

He was also interested in jazz. This interest led to his writing a piano-vocal composition entitled Jazz dans la nuit, which was similar in its inspiration to other jazz-inspired works such as the second movement of Ravel’s Violin Sonata, or Milhaud’s La création du monde.

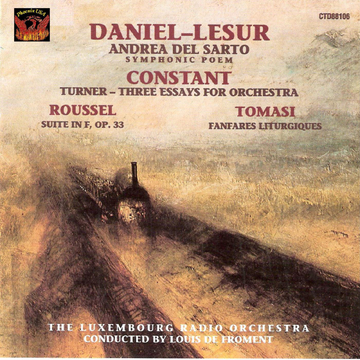

Roussel’s most important works were the ballets Le festin de l’araignée, Bacchus et Ariane, and Aeneas and the four symphonies, of which the Third in G minor, and the Fourth in A major, are highly regarded and epitomize his mature neoclassical style. His other works include numerous ballets, orchestral suites, a piano concerto, a concertino for cello and orchestra, a psalm setting for chorus and orchestra, incidental music for the theatre, and much chamber music, solo piano music, and songs.

In 1929, one French critic, Henry Prunières, described Roussel’s search for his own voice:[3]

Albert Roussel for a long period sought his true self among varied and contradictory influences. He seemed to waver between the tendencies of Cesar Franck and Vincent d’Indy and those of Claude Debussy. The violin sonata, the trio, the Poème de la Forêt derived more or less directly from the Franckian school, the Festin de l’Araignée and the Evocations from Debussyan impressionism; and yet the hand of Albert Roussel alone could have written this music, at once so subtle and so firmly fixed in its design… With Padmâvatî, the new Roussel begins to realize his possibilities and his individual technique… Then came works of perfect homogeneity and notable originality. The composer no longer is seeking his way – he has found it. The Prélude pour une Fête de Printemps, the suite in F, the concerto, and finally the Psalm No. 80 are the masterpieces which mark the last stage of this great artist.

Arturo Toscanini included the suite from the ballet Le festin de l’araignée in one of his broadcast concerts with the NBC Symphony Orchestra. Rene Leibowitz recorded that suite in 1952 with the Paris Philharmonic, and Georges Prêtre recorded it with the Orchestre National de France for EMI in 1984.

One brief assessment of his career says:[4]

Roussel will never attain the popularity of Debussy or Ravel, as his work lacks sensuous appeal….yet he was an important and compelling French composer. Upon repeated listening, his music becomes more and more intriguing because of its subtle rhythmic vitality. He can be alternately brilliant, astringent, tender, biting, dry, and humorous. His splendid Suite for Piano (Op. 14, 1911) shows his mastery of old dance forms. The ballet scores Le Festin de l’araignée (The Spider’s Feast Op. 17, 1913) and Bacchus et Ariane (Op. 43, 1931) are vibrant and pictorial, while the Third and Fourth Symphonies are among the finest contributions to the French symphony.

One 21st-century critic, in the course of discussing the Third Symphony, wrote:[5]

For the general public, Roussel remains almost famous, his work just beyond the pool of repertory universally drawn from. His music, said another way, walks the line between the memorable and the impossible to forget. The writing sets unrelated keys against one another but eventually seeks strong tonal centers; in other words, it can bark and growl but in the end wags its tail. The Vivace movement is a carnival of exuberant energies. Roussel was more than just an anti-19th-century dissident.