Jolson, Al

Al Jolson (born Asa Yoelson; c. 1885 – October 23, 1950) was an American singer, comedian, actor, and vaudevillian. Self-billed as “The World’s Greatest Entertainer”,[1] Jolson is credited with being America’s most famous and highest-paid star of the 1920s.[2] He was known for his “shamelessly sentimental, melodramatic approach”,[3] and for popularizing many of the songs he performed.[4] Jolson has been referred to by modern critics as “the king of blackface performers”.[5][6]

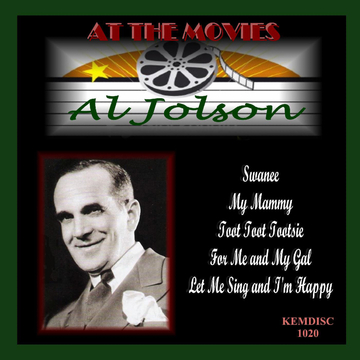

Although best remembered today as the star of the first talking picture, The Jazz Singer (1927), he starred in a series of successful musical films during the 1930s. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he was the first star to entertain troops overseas during World War II. After a period of inactivity, his stardom returned with The Jolson Story (1946), for which Larry Parks played Jolson, with the singer dubbing for Parks. The formula was repeated in a sequel, Jolson Sings Again (1949). In 1950, he again became the first star to entertain GIs on active service in the Korean War, performing 42 shows in 16 days. He died weeks after returning to the U.S., partly owing to the physical exhaustion from the performance schedule. Defense Secretary George Marshall posthumously awarded him the Medal for Merit.[7]

According to music historian Larry Stempel, “No one had heard anything quite like it before on Broadway.” Stephen Banfield wrote that Jolson’s style was “arguably the single most important factor in defining the modern musical”.[8]

With his dynamic style of singing jazz and blues, he became widely successful by extracting traditionally African-American music and popularizing it for white American audiences who were otherwise not receptive to the originators.[9] Despite his promotion and perpetuation of black stereotypes,[10] his work was often well-regarded by black publications and he has been credited for fighting against black discrimination on Broadway[5] as early as 1911. In an essay written in 2000, music critic Ted Gioia remarked, “If blackface has its shameful poster boy, it is Al Jolson”, showcasing Jolson’s complex legacy in American society.[11]

The Jazz Singer[edit]

Before The Jazz Singer, Jolson starred in the talking film A Plantation Act. This simulation of a stage performance by Jolson was presented in a program of musical shorts, demonstrating the Vitaphone sound-film process. The soundtrack for A Plantation Act was considered lost in 1933 but was found in 1995 and restored by The Vitaphone Project.[30]

Warner Bros. picked George Jessel for the role, as he had starred in the Broadway play. When Sam Warner decided to make The Jazz Singer a musical with the Vitaphone, he knew that Jolson was the star he needed. He told Jessel that he would have to sing in the movie, and Jessel balked, allowing Warner to replace him with Jolson. Jessel never got over it and often said that Warner gave the role to Jolson because he agreed to help finance the film.

Harry Warner‘s daughter, Doris, remembered the opening night, and said that when the picture started she was still crying over the loss of her beloved uncle Sam. He was planning to be at the performance but died suddenly at the age of 40, the day before. But halfway through the 89-minute movie she began to be overtaken by a sense that something remarkable was happening. Jolson’s “Wait a minute” line provoked shouts of pleasure and applause from the audience, who were dumbfounded by seeing and hearing someone speak on a film for the first time. So much so that the double-entendre was missed at first. After each Jolson song, the audience applauded. Excitement mounted as the film progressed, and when Jolson began his scene with Eugenie Besserer, “the audience became hysterical.”[31]

According to film historian Scott Eyman, “by the film’s end, the Warner brothers had shown an audience something they had never known, moved them in a way they hadn’t expected. The tumultuous ovation at curtain proved that Jolson was not merely the right man for the part of Jackie Rabinowitz, alias Jack Robin; he was the right man for the entire transition from silent fantasy to talking realism. The audience, transformed into what one critic called, ‘a milling, battling mob’ stood, stamped, and cheered ‘Jolson, Jolson, Jolson!'”[32]

Vitaphone was intended for musical renditions, and The Jazz Singer follows this principle, with only the musical sequences using live sound recording. The moviegoers were electrified when the silent actions were interrupted periodically for a song sequence with real singing and sound. Jolson’s dynamic voice, physical mannerisms, and charisma held the audience spellbound. Costar May McAvoy, according to author A. Scott Berg, could not help sneaking into theaters day after day as the film was being run. “She pinned herself against a wall in the dark and watched the faces in the crowd. In that moment just before ‘Toot, Toot, Tootsie,’ she remembered, ‘A miracle occurred. Moving pictures really came alive. To see the expressions on their faces, when Joley spoke to them … you’d have thought they were listening to the voice of God.'”[33] “Everybody was mad for the talkies,” said movie star Gregory Peck in a Newsweek interview. “I remember ‘The Jazz Singer,’ when Al Jolson just burst into song, and there was a little bit of dialogue. And when he came out with ‘Mammy,’ and went down on his knees to his Mammy, it was just dynamite.”[34]

This opinion is shared by Mast and Kawin:

this moment of informal patter at the piano is the most exciting and vital part of the entire movie … when Jolson acquires a voice, the warmth, the excitement, the vibrations of it, the way its rambling spontaneity lays bare the imagination of the mind that is making up the sounds … [and] the addition of a Vitaphone voice revealed the particular qualities of Al Jolson that made him a star. Not only the eyes are a window on the soul.[35]

Poster for Hallelujah, I’m a Bum with unused title

The Singing Fool (1928)[edit]

With Warner Bros. Al Jolson made his first “all-talking” picture, The Singing Fool (1928), the story of an ambitious entertainer who insisted on going on with the show even as his small son lay dying. The film was even more popular than The Jazz Singer. “Sonny Boy“, from the film, was the first American record to sell one million copies.

Jolson continued to make features for Warner Bros. similar in style to The Singing Fool. These included Say It with Songs (1929), Mammy (1930), and Big Boy (1930). A restored version of Mammy, with Jolson in Technicolor sequences, was first screened in 2002.[36] Jolson’s first Technicolor appearance was a cameo in the musical Showgirl in Hollywood (1930) from First National Pictures, a Warner Bros. subsidiary. However, these films gradually proved a cycle of diminishing returns due to their comparative sameness, the regal salary that Jolson demanded, and a shift in public taste away from vaudeville musicals as the 1930s began. Jolson returned to Broadway and starred in the unsuccessful Wonder Bar.[37]

Hallelujah, I’m a Bum/Hallelujah, I’m a Tramp[edit]

Warner Bros. allowed him to make Hallelujah, I’m a Bum with United Artists in 1933. It was directed by Lewis Milestone and written by Ben Hecht. Hecht was also active in the promotion of civil rights: “Hecht film stories featuring black characters included Hallelujah, I’m a Bum, co-starring Edgar Connor as Jolson’s sidekick, in a politically savvy rhymed dialogue over Richard Rodgers music.”[38]

The New York Times reviewer wrote, “The picture, some persons may be glad to hear, has no Mammy song. It is Mr. Jolson’s best film and well it might be, for that clever director, Lewis Milestone, guided its destiny … a combination of fun, melody and romance, with a dash of satire….”[39] Another review added, “A film to welcome back, especially for what it tries to do for the progress of the American musical….”[40]

Wonder Bar (1934)[edit]

In 1934, he starred in a movie version of his earlier stage play Wonder Bar, co-starring Kay Francis, Dolores del Río, Ricardo Cortez, and Dick Powell. The movie is a “musical Grand Hotel, set in the Parisian nightclub owned by Al Wonder (Jolson). Wonder entertains and banters with his international clientele.”[41] Reviews were generally positive: “Wonder Bar has got about everything. Romance, flash, dash, class, color, songs, star-studded talent and almost every known requisite to assure sturdy attention and attendance…. It’s Jolson’s comeback picture in every respect.”;[42] and, “Those who like Jolson should see Wonder Bar for it is mainly Jolson; singing the old reliables; cracking jokes which would have impressed Noah as depressingly ancient; and moving about with characteristic energy.”[43]

The Singing Kid (1936)[edit]

Jolson’s last Warner vehicle was The Singing Kid (1936), a parody of Jolson’s stage persona (he plays a character named Al Jackson) in which he mocks his stage histrionics and taste for “mammy” songs—the latter via a number by E. Y. Harburg and Harold Arlen titled “I Love to Singa“, and a comedy sequence with Jolson doggedly trying to sing “Mammy” while The Yacht Club Boys keep telling him such songs are outdated.[44]

According to jazz historian Michael Alexander, Jolson had once griped that “People have been making fun of Mammy songs, and I don’t really think that it’s right that they should, for after all, Mammy songs are the fundamental songs of our country.” (He said this, in character, in his 1926 short A Plantation Act.) In this film, he notes, “Jolson had the confidence to rhyme ‘Mammy’ with ‘Uncle Sammy'”, adding “Mammy songs, along with the vocation ‘Mammy singer’, were inventions of the Jewish Jazz Age.”[45]

The film also gave a boost to the career of black singer and bandleader Cab Calloway, who performed a number of songs alongside Jolson. In his autobiography, Calloway writes about this episode:

I’d heard Al Jolson was doing a new film on the Coast, and since Duke Ellington and his band had done a film, wasn’t it possible for me and the band to do this one with Jolson. Frenchy got on the phone to California, spoke to someone connected with the film and the next thing I knew the band and I were booked into Chicago on our way to California for the film, The Singing Kid. We had a hell of a time, although I had some pretty rough arguments with Harold Arlen, who had written the music. Arlen was the songwriter for many of the finest Cotton Club revues, but he had done some interpretations for The Singing Kid that I just couldn’t go along with. He was trying to change my style and I was fighting it. Finally, Jolson stepped in and said to Arlen, ‘Look, Cab knows what he wants to do; let him do it his way.’ After that, Arlen left me alone. And talk about integration: Hell, when the band and I got out to Hollywood, we were treated like pure royalty. Here were Jolson and I living in adjacent penthouses in a very plush hotel. We were costars in the film so we received equal treatment, no question about it.[46]

The Singing Kid was not one of the studio’s major attractions (it was released by the First National subsidiary), and Jolson did not even rate star billing. The song “I Love to Singa” later appeared in Tex Avery‘s cartoon of the same name. The movie also became the first important role for future child star Sybil Jason in a scene directed by Busby Berkeley. Jason remembers that Berkeley worked on the film although he is not credited.[47]

Rose of Washington Square (1939)[edit]

His next movie—his first with Twentieth Century-Fox—was Rose of Washington Square (1939). It stars Jolson, Alice Faye and Tyrone Power, and included many of Jolson’s best known songs, although several songs were cut to shorten the movie’s length, including “April Showers” and “Avalon“. Reviewers wrote, “Mr Jolson’s singing of Mammy, California, Here I Come and others is something for the memory book”[48] and “Of the three co-stars this is Jolson’s picture … because it’s a pretty good catalog in anybody’s hit parade.”[49] The movie was released on DVD in October 2008. 20th Century Fox hired him to recreate a scene from The Jazz Singer in the Alice Faye-Don Ameche film Hollywood Cavalcade.[citation needed] Guest appearances in two more Fox films followed that same year, but Jolson never starred in a full-length feature film again.

The Jolson Story[edit]

After the George M. Cohan film biography, Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), Hollywood columnist Sidney Skolsky believed that a similar film could be made about Al Jolson. Skolsky pitched the idea of an Al Jolson biopic and Harry Cohn, the head of Columbia Pictures agreed. It was directed by Alfred E. Green, best remembered for the pre-Code Baby Face (1933), with musical numbers staged by Joseph H. Lewis. With Jolson providing almost all the vocals, and Columbia contract player Larry Parks playing Jolson, The Jolson Story (1946) became one of the biggest box-office hits of the year.[50] In a tribute to Jolson Larry Parks wrote, “Stepping into his shoes was, for me, a matter of endless study, observation, energetic concentration to obtain, perfectly if possible, a simulation of the kind of man he was. It is not surprising, therefore, that while making The Jolson Story, I spent 107 days before the cameras and lost eighteen pounds in weight.”[51]

From a review in Variety:

But the real star of the production is that Jolson voice and that Jolson medley. It was good showmanship to cast this film with lesser people, particularly Larry Parks as the mammy kid…. As for Jolson’s voice, it has never been better. Thus the magic of science has produced a composite whole to eclipse the original at his most youthful best.[52]

Parks received an Oscar nomination for Best Actor. Although the 60-year-old Jolson was too old to play a younger version of himself in the movie, he persuaded the studio to let him appear in one musical sequence, “Swanee“, shot entirely in long shot, with Jolson in blackface singing and dancing onto the runway leading into the middle of the theater. In the wake of the film’s success and his World War II tours, Jolson became a top singer among the American public once more.[53][54] Decca signed Jolson and he recorded for Decca from 1945 until his death, making his last commercial recordings for the company.

According to film historian Krin Gabbard, The Jolson Story goes further than any of the earlier films in exploring the significance of blackface and the relationships that whites have developed with blacks in the area of music. To him, the film seems to imply an inclination of white performers, like Jolson, who are possessed with “the joy of life and enough sensitivity, to appreciate the musical accomplishments of blacks”.[55] To support his view he describes a significant part of the movie:

While wandering around New Orleans before a show with Dockstader’s Minstrels, he enters a small club where a group of black jazz musicians are performing. Jolson has a revelation, that the staid repertoire of the minstrel troupe can be transformed by actually playing black music in blackface. He tells Dockstader that he wants to sing what he has just experienced: ‘I heard some music tonight, something they call jazz. Some fellows just make it up as they go along. They pick it up out of the air.’ After Dockstader refuses to accommodate Jolson’s revolutionary concept, the narrative chronicles his climb to stardom as he allegedly injects jazz into his blackface performances…. Jolson’s success is built on anticipating what Americans really want. Dockstader performs the inevitable function of the guardian of the status quo, whose hidebound commitment to what is about to become obsolete reinforces the audience’s sympathy with the forward-looking hero.[56]

This has been a theme which was traditionally “dear to the hearts of the men who made the movies”.[56] Film historian George Custen describes this “common scenario, in which the hero is vindicated for innovations that are initially greeted with resistance…. [T]he struggle of the heroic protagonist who anticipates changes in cultural attitudes is central to other white jazz biopics such as The Glenn Miller Story (1954) and The Benny Goodman Story (1955)”.[57] “Once we accept a semantic change from singing to playing the clarinet, The Benny Goodman Story becomes an almost transparent reworking of The Jazz Singer … and The Jolson Story.”[56]

Jolson Sings Again (1949)

A sequel, Jolson Sings Again (1949), opened at Loew‘s State Theatre in New York and received positive reviews: “Mr. Jolson’s name is up in lights again and Broadway is wreathed in smiles”, wrote Thomas Pryor in The New York Times. “That’s as it should be, for Jolson Sings Again is an occasion which warrants some lusty cheering….”[58] Jolson did a tour of New York film theaters to plug the movie, traveling with a police convoy to make timetables for all showings, often ad libbing jokes and performing songs for the audience. Extra police were on duty as crowds jammed the streets and sidewalks at each theater Jolson visited.[59] In Chicago, a few weeks later, he sang to 100,000 people at Soldier Field, and later that night appeared at the Oriental Theatre with George Jessel where 10,000 people had to be turned away.[58]

Radio and television

Jolson had been a popular guest star on radio since its earliest days, including on NBC’s The Dodge Victory Hour (January 1928), singing from a New Orleans hotel to an audience of 35 million via 47 radio stations. His own 1930s shows included Presenting Al Jolson (1932) and Shell Chateau (1935), and he was the host of the Kraft Music Hall from 1947 to 1949, with Oscar Levant as a sardonic, piano-playing sidekick. Jolson’s 1940s career revival was nothing short of a success despite the competition of younger performers such as Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra, and he was voted the “Most Popular Male Vocalist” in 1948 by a poll in Variety. The next year, Jolson was named “Personality of the Year” by the Variety Clubs of America. When Jolson appeared on Bing Crosby’s radio show, he attributed his receiving the award to his being the only singer of any importance not to make a record of “Mule Train“, which had been a widely covered hit of that year (four different versions, one of them by Crosby, had made the top ten on the charts). Jolson joked about how his voice had deepened with age, saying “I got the clippetys all right, but I can’t clop like I used to.”[citation needed]

In addition to his contribution to motion pictures as a performer, he is responsible for the discovery of two major stars of the golden age of Hollywood. He purchased the rights to a play he saw on Broadway and then sold the movie rights to Jack Warner (Warner Brothers which was the studio that had made The Jazz Singer) with the stipulation that two of the original cast members reprise their roles in the movie. The play became the movie Penny Arcade, and the actors were Joan Blondell and James Cagney, who both went on to become contract players for the studio. The two were major ingredients in gangster movies, which were lucrative for the studio.

Cagney won his Academy Award for his role in Warner Brothers’ Yankee Doodle Dandy, which at the time was the studio’s highest-grossing movie. The award is rarely given to performers in musicals. Ironically, Cagney, who became known for his tough guy movie roles, also made a contribution to movie musicals, like the man who had discovered him. While Jolson is credited for appearing in the first movie musical, Cagney’s Academy Award-winning movie was the first movie Ted Turner chose to colorize.

When Jolson appeared on Steve Allen‘s KNX Los Angeles radio show in 1949 to promote Jolson Sings Again, he offered his curt opinion of the burgeoning television industry: “I call it smell-evision.” Writer Hal Kanter recalled that Jolson’s own idea of his television debut would be a corporate-sponsored, extra-length spectacular that would feature him as the only performer, and would be telecast without interruption. Even though he had several TV offers at the time, Jolson was apprehensive about how his larger than life performances would come across in a medium as intimate as television. He finally relented in 1950, when it was announced that Jolson had signed an agreement to appear on the CBS television network, presumably in a series of specials. However, he died suddenly before production began.[60]